One of the essential features of the development of the movement was the establishment of guilds and societies, binding together artists, craftsmen and designers. These groups were similar to the medieval guilds of tradesmen, but an important difference was that they were made up of different trades or crafts working together in an equal partnership of arts and crafts.

Artists sculptors, designers, architects, craftsmen in stained glass, pottery and other crafts were all equally involved and no art or craft was considered superior to any other. The Guilds helped to bring artist and craftsmen together and helped to publicise the movement through meetings, lectures, exhibitions and demonstrations of particular crafts. The Studio magazine, from 1893 onwards regularly reviewed Arts and Crafts exhibitions and featured articles on individual designers and techniques such as repousse copper work, embroidery and furniture design. Articles featuring the work of Ballie Scott, Voysey, Ashbee, Glasgow School and other leading figures were frequently included with illustrations of their designs and finished work.

One of the first attempts to establish a Guild was Ruskin's Guild of St George which was set up in 1871. The Guild failed in its ambitious aims which included taking a stand against the industrialisation of society, seeking to replace it by a medieval order with a common interest in the quality of life and work.

A more realistic and practical effort was a commercial venture led by Authur Heygate Mackmurdo who established the Century Guild of Artists in 1882. Mackmurdo, an architect who had had taught himself metal work, carving, furniture making, and embroidery, was one of the founding members. Whilst he had become a skilled designer himself he recognised his limitations and realised the need to recruit craftsmen already working in the applied arts to join together in a commercial venture. In 1884 'The Hobby Horse' magazine was started by the Guild, to encourage the revival of arts and crafts.

The first Arts and Crafts exhibitions.

In 1884 the Art Workers Guild was founded by a group of prominent Arts and Crafts architects who were later joined by members of 'The Fifteen', a group of artists architects, craftsmen and designers. The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society developed out of the Art Workers Guild, holding its first exhibition in 1888, which was when the term 'Arts and Crafts' was first used to describe the growing movement. Exhibitions were held periodically until the outbreak of the first world war in 1914.

A. H. Mackmurdo described in his diary the aims of the first Arts and Crafts exhibition in 1888, which included:

-

To show the British public what could be done by their contemporary fellow craftsmen in making beautiful things for the homes of simple and gentle folk.

-

To revive the desire for beauty in the things of everyday use...

-

To arouse among art workers an emulation to excel by placing the work of various designers and craftsmen side by side.

-

To turn industry in the direction of producing such kind of decorative form as can be produced without detriment by mechanical process.

The School of Handicraft.

The School of Handicraft started in 1887 and the Guild of Handicraft started in 1888 were largely the work of Charles Robert Ashbee. Ashbee, like several of the leading figures was from a wealthy background, educated at Cambridge and started his career as an architect. Many of the most admired products of the Guild, metal work and jewellery in particular were designed by Ashbee. The Guild was based at Essex House in Mile End Road in London until 1902 when it moved to Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds.

The Guilds and Societies which started within the last 15 years of the nineteenth century were the forerunners of a much wider movement which flourished through to the 1930's. At one level this included the establishment of artistic communities where artists and craftsmen lived and worked together as in Newlyn, Keswick and Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds. At a broader level the movement encompassed a whole range of local societies, exhibitions, schools and night classes teaching and encouraging handicrafts and artistic techniques.

There were high minded ideals behind the establishment of community crafts industries, socialist or philanthropic notions for regenerating rural communities where the traditional industry had declined. The Craft Revival was also fuelled by the new ideals of Arts Schools and Colleges in London, Liverpool, Birmingham and Glasgow where there was a push to develop applied art. This involved forging links with local industries, the training of local artisans and supporting the development of education in art and craft for the widest possible audiences.

As well the Academic influence there were commercial ventures established to help sell arts and crafts products. The Home Arts Industries for example was founded in 1884 to provide a London shop for craft products and to coordinate the efforts of craft workers across the country. Haslemere Peasant Industries was set up by Godfrey Blount in 1896 as an artistic community in Surrey and as marketing organisation for local workshops with a London shop for the sale of work.

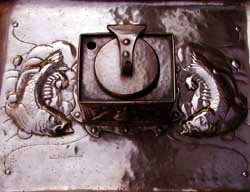

The articles produced by the Guilds and Societies varied in quality with some exceptional pieces being created. Much sought after today is the metalwork in copper which was crafted at the Newlyn School established in 1890 by John MacKenzie. Copper chargers, vases, and other decorative items which were embossed with designs of fish, and other natural and fanciful sea creatures are some the best examples of 'repousse 'work in England. Items were sold at Penzance and to a wider market which included Liberty of London. Similar work though in usually flat plate form was produced by the Keswick School of Industrial Art.

The broad range of people involved in creating objects in arts and crafts style has meant that a great number of pieces of furniture, metalwork embroidery, stained glass and decorative items have survived and appear on the market for sale. This has encouraged a broader base for collectors, affordable ' amateur' pieces being available in most town and cities for tens rather than hundreds of pounds.